Dodo Bird of Mauritius: From Discovery to Extinction

Native to the small island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, the chubby flightless Dodo bird (Raphus cucullatus) became famous through its own extinction. Discovered by the Dutch in the 16th century, the creature disappeared from the Earth’s surface within some 80 years of its discovery. Today still, the Dodo, its environment, ecological function and extinction interests many scientists. Yet, since only a few bones, some tissue, a small number of paintings and unscientific records of the bird exists, its study remains complicated.

Historical account of the Dodo’s presence on Mauritius

Though the early Arabs and Portuguese probably discovered Mauritius, it was the Dutch who took records of dodos on the island.

Back then, it was customary for sailors to take notes of topographical details, shipping routes and safe harbours when landing on new land. Oftentimes, professional artists also embarked on the voyages. These notes and drawings were important for future expeditions, scientists and book publishers.

Presently, these accounts and drawings form the basis for understanding the ecology of the Dodo.

Describing Dodos as ‘Penguins’

The first account of the Dodo stems from Heyndrick Dircksz Jolinck’s record who led one of the expeditions to Mauritius in 1598. He described the dodo for the first time as

‘large birds, with wings as large as of a pigeon, so that they could not fly and were named penguins by the Portuguese. These particular birds have a stomach so large that it could provide two men with a tasty meal and was actually the most delicious part of the bird’ (Moree 1998, p. 12).

‘Penguins’ here probably means ‘pinion’, the Portuguese word meaning ‘clipped wings’ referring to the small wings of the Dodo.

Dodos become rare

In 1601-1603, Admiral Wolphert Harmenzoon stopped off at Mauritius in the south-west. He then described the dodos as being common on a small offshore islet, most probably referring to Ile aux Benitiers.

Additionally, in 1602, West-Zanen, who visited Mauritius earlier on, also captained a voyage to the island. He took notes of capturing the birds and salting them on board. Following these, various accounts chronicle the introduction of foreign animals on Mauritius and the damage they caused.

Only one Dutch sailor in 1631 noted the diet of the Dodo: raw fruit.

In 1628-1634, Peter Mundy, an avid island fauna observer visited Mauritius. He then remarked that he had initially seen the big creatures in Surat, India. He did not actually land but this probably suggested that the Dutch were also exporting the dodos.

Live Dodo in the streets of England

Interestingly in 1628, Emanuell Altham made an account of sending a live Dodo to his brother in England in two letters. Whether the animal really reached its destination, alive or dead is unknown. Altham also mentioned of the rareness of the bird at that particular point in time as well as the large numbers of introduced animals.

One year later, Thomas Herbert, a learned traveller and writer, described his encounter with the Dodo accompanied by an illustration of the creature. Strikingly Sir Hamon L’Estrange mentioned encountering a live Dodo in the streets of London in 1638. This thus proved that the bird indeed reached Europe.

Finally, the last authentic mention of this amazing creature comes from Evertszen in 1662. He and his friends survived a shipwreck near Mauritius. They apparently chased and caught the animals on some offshore islets off the west coast.

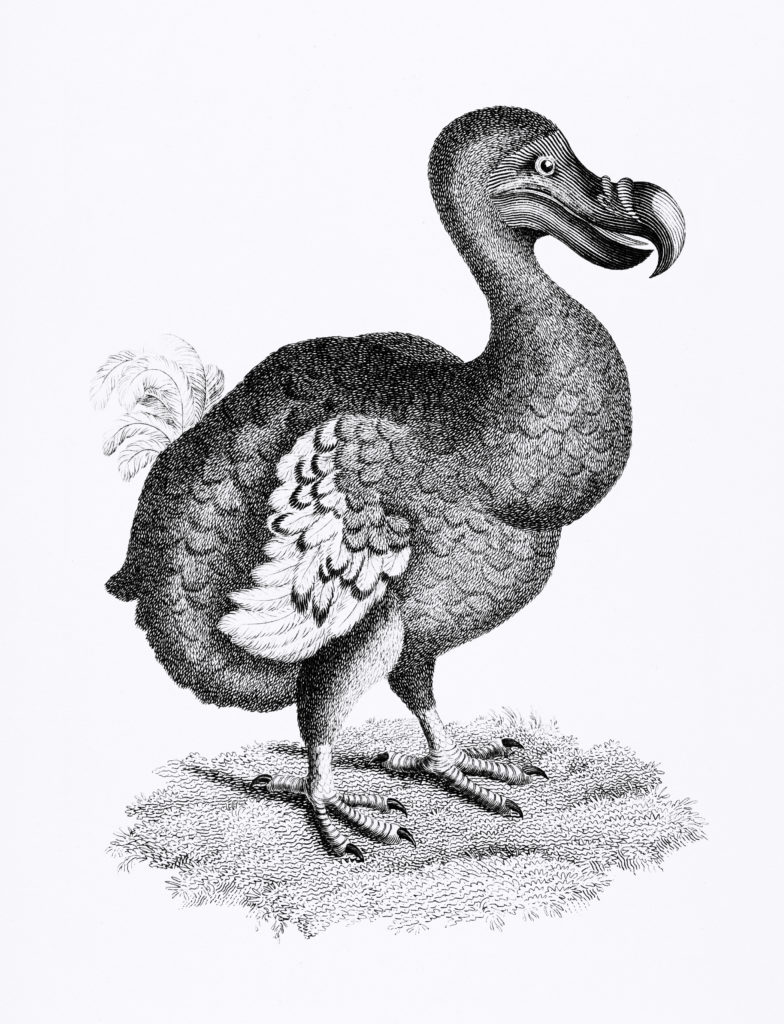

What did the Dodo look like?

Basically, the Dodo is depicted as a tan-coloured, stout, obese bird with small wings. At first, some scientists related the bird to the Columbiformes (pigeons and doves) but others ridiculed the idea.

However, subsequent DNA analyses proved that indeed the Dodo, as well as the extinct Solitaire on Rodrigues island, are from the Columbiformes family. What’s more, they also originate from the same ancestor as the Asian Nicobar Pigeon (Coleonas nicobarica).

Physical appearance of the dodo

Richard Owen first reconstructed the bird in 1866. Based on Edward’s Dodo painting, he constructed it as a squat obese bird. After obtaining more skeletons in 1872, he re-constructed an upright, more real-life representation.

The particular posture of the animal is due to the loss of its flight muscles. Nevertheless, the small wings were useful for balancing and it could easily outrun a man amongst rocks.

Now when it comes to colour, it is difficult to be precise. The most reliable painting depicts it as tan though. Also, unfortunately, it is impossible to state the exact height and weight of the bird because of the lack of concrete evidence. Skeletal construction puts the height of the animal at around 3 feet while modern analytical methods estimate a body mass between 8-18 kg.

Physical evidence of the Dodo

As the Dodo only lived on Mauritius with probably one sighting in Surat and London, it was questionable if the bird indeed existed.

Its first physical evidence is a skull from a rare object collector, Bernardus Paludanus of Enkhuizen, dating to 1840. How the skull got into Paludanus’ possession is unclear but to date, the Copenhagen skull as it is called is the oldest Dodo fossil.

It is based on this skull that scientists formulated the hypothesis that the Dodo was a giant flightless pigeon. This was followed by Clusius’ description of a dodo leg in 1605, and Crosfield’s notes on the birds in his diary in 1634.

Exhibition of Dodo bones in British Museums

Eventually, the British exhibited the Dodo that L’Estrange saw in London in the Tradescant museum in 1656. And in 1659, the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford took hold of it. After that, the Royal Society exhibited a second dodo foot named the ‘London or British Museum foot’ at the British Museum in 1665-1681.

Also, Roelandt Savery made the most famous and look-alike painting of the Dodo and called it ‘Edward’s Dodo’. The British Museum exhibited this painting and the dodo foot until the late 1840s.

Following Hugh Strickland and Alexander Melville’s monograph on the creature in 1848, scientific interest in the Dodo sparked again.

Discovery of the first Dodo bones on Mauritius

This enthusiasm led George Clark to discover the first Dodo bones at Mare aux Songes on the south coast of Mauritius in 1865. He was a Master of the Diocesan School on Mauritius at that time. Incidentally, it was also the same year that Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) published his book ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’. Illustrator Sir John Tenniel immortalized the magnificent creature in that book based on Edward’s Dodo.

With the discovery of the bones, excavation began fervently and within the year, almost complete skeletons from Mare aux Songes were sent to England. Somewhere between 1890-1907, Etienne Thirioux discovered the almost complete Dodo skeleton at an unknown location on Mauritius.

Paul Carié was the last one to extract dodo bones from Mare aux Songes in 1902. After that, the site was filled to combat malaria.

New dodo bones discovered on Mauritius

In 1995, a Japanese team excavated the Mare aux Songes site once more in collaboration with Mauritian Institutes. And once more, they dug out some dodo bones. But some unfortunate circumstances beheld both principal investigators of the project and the results were not published.

In 2005, other researchers studied Mare aux Songes as part of an archaeological project to reconstruct human settlement on Mauritius. Cores revealed a fascinating amount of information on the flora and fauna of Mauritius long before it was discovered. This led to the initiation of the Dodo Research Programme for understanding the original biota of Mauritius. Archaeological works took place over the period 2005 to 2011. This eventually led to the discovery of the pelvis and some leg bones of a dodo bird.

Extinction of the Dodo

There is a lot of speculation around the extinction of the Dodo. Hypotheses like deforestation, stupidity of the bird, lack of capacity to run and overhunting amongst others are quite common.

Yet, many of these reasons are just opinions and unrelated to the situation at that time.

Thus, based on historical accounts, the most likely reason for the extinction of the bird is the introduction of exotic animals. They damaged the birds’ environment and limited their reproductive abilities.

Some of the reasons why the Dodo disappeared

The big dodo bird was anything but stupid. In fact, the animal had survived on Mauritius for thousands of years despite extreme climatic events. Consequently, it developed characteristics to survive in that type of environment. For instance, it had a strong beak to protect itself and its chicks. It could also run fast in the forest and even had stomach gizzards that could crush and digest tough fruits. But since the dodo did not have any direct predator, it was not afraid of humans. As a result, hunters easily captured and killed them.

Also, despite the fact that sailors hunted the dodo for its meat, they did not really appreciate its quality. When they brought other animals like cows, deer, pigs and goats to Mauritius, hunters opted for the common game. What’s more, hunting was also restricted to the coastal regions.

It is worth to note that at any time the Dutch were on the island, the human population was very low, not exceeding 100 people. Also, the forest at that time was quite thick and impenetrable. Consequently, it was difficult for sailors to hunt dodos inside the canopy.

Moreover, the Dutch indeed cleared some forest land for agriculture, settlement and to export ebony trees. But only 5% of the forest was damaged when they finally departed.

The true reason the Dodo disappeared

Many accounts describe the infestation and damage of the black rats (Rattus rattus) in Mauritius. These pests reached the island onboard Dutch ships and had a significant impact on the biodiversity of Mauritius as a whole. Scientists suggest that the black rats competed with Dodos for food especially after cyclones when food was scarce. Additionally, foreign animals especially pigs and monkeys made matters worse for the dodos. They destroyed their nests, understory forest and preyed on their eggs and chicks.

Last sighting of the Dodo

Also, the last mention of the Dodo on Mauritius was in 1681 by Benjamin Harris on his homeward journey to England. Where matters currently stand, it is difficult to ascertain when exactly the Dodo went extinct. Nonetheless, it is believed to be somewhere in the late 17th century.

Cautionary note on the Dodo

The Dodo is the subject of interest of many historians, scientists, ornithologists, painters and book publishers since its discovery. Consequently, many historical records and paintings have been plagiarized. Testimonies about dodo sightings have also been feigned when properly analyzed.

As such, it is complex to state with certainty what happened to the Dodo, why, where and when it happened. We can only understand bits and pieces of this great creature’s journey in Mauritius.

References

- Hume, J.P., 2006. The history of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and the penguin of Mauritius. Historical Biology, 18(2), pp.69-93.

- Moree P., 1998. A concise history of Dutch Mauritius,1598–1710. London and New York: Kegan Paul International. p 127.

Pingback: Coffee: History, Types, Benefits, Problems and Fair Trade - Yo Nature

Pingback: Poaching – the cruelty driven business - Yo Nature

Pingback: Biodiversity (Flora and Fauna) of Mauritius - Yo Nature

Pingback: Monkey Trade in Mauritius: Controversies and Benefits - Yo Nature

Pingback: Offshore islets of Mauritius: National Parks and Nature Reserves - Yo Nature